Archives

The meaning of life is that it stops ~ Frantz Kafka

Often when speaking with someone about his or her plans or their present situation I am tempted to say: “this is a great strategy provided you are an immortal”. We constantly move among several spheres at the same time; the inner world, the outside world, subconscious and conscious, our family, community, the world at large, the past, the present, the future. For the fortunate among us, the rapid transition is imperceptible: others get stuck in one sphere, or emotionally bleed on their jagged edges as they pass through. But we all inhabit those spheres thanks to our consciousness.

Our inner world, our memories, and our place in the community would all disappear with our demise. The rest of the spheres would continue without us. That is one of the facts we must grapple with, as depressing and painful as it is. It is in fact so painful to think about, that most of us do our best to ignore it.

When do we become aware of our own mortality? As infants, we have no concept of anything other than our inner world, some hazy surrounding, and no clear memories. Then, at age 3, we start to understand the impermanence of certain things and become fearful of separation from our parents. But as children we are mostly worried about out parents’ mortality and not our own. In our twenties we realize our own mortality but feel immortal. It is in your thirties, as you feel the first bites of time, when you finally realize: My time here is limited. That of course is the price we pay for our consciousness. An animal becomes aware of its death only when it is actually dying. We humans, have to bear the cross of mortal fear, always looming in the background of our mind.

Now, that the proverbial “fear of death” becomes a reality, we must find a way to cope with it. The most common strategy we use is denial; we deny/ignore our mortality. This, most universal defense of denial, is an important pillar of our notion of hope, and is very welcome. Hopefulness permits us to be imaginative, daring and adventurous. Much of what we are committed to in the present is an outcome of a decision made by our younger, less informed self. In fact, we make the most important decisions – such as partner and career – when we still believe in immortality. We commit to the entire trajectory of our life at an age when the future lies ahead boundless and mysterious like an ocean, and the past is palpably close.

All of the above are totally normal features of life. We commonly set during the immortality phase the two anchors of life, work and love, to mitigate this daredevil attitude of youth. Like all anchors they can ideally ground us, or, as often happens, immobilize us. It depends on the elasticity of the tether. That is to say your ability to shift smoothly from denial to reality when the situation calls for. Ideally, your life should have strong anchors and elastic long tethers. Your relationship and your work should ground you rather than immobilize you. However, some people get carried away with a successful denial, and start behaving as if they can linger indefinitely in a situation that is bringing them down, waiting for the next act.

Sooner or later, as your future’s shrinking act quickens, your ability to deny the inevitable wears thin. Your past, once a source of joy and embarrassment, trails behind you dense with vague, almost forgotten memories, like an aging dog. You become more experienced, perhaps wiser, and the wheel of time starts spinning faster. You realize that you must evaluate your life before it is too late.

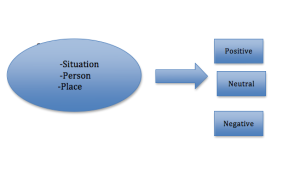

I developed a mini scale I call “The Dr. K. existential Scale” to evaluate one’s life on an ongoing, daily basis. In its crudest form it asks one question concerning your immediate environment: How does this person/ place/ activity influence your life: Does it have a positive, neutral or negative impact on you?

The scale looks something like that:

Of course it is very simplistic: Your relations with a person, a place, or a situation tend to be more complex than merely negative positive and neutral. In fact, even the mere notions of negative and positive are shifting: what is good today can become horrible tomorrow etc.

However, by asking this little question on a regular basis you can derive two major benefits: 1. You will get used to examining your life and your choices and 2. You will start realizing something very interesting about your life: Namely, you do not need to constantly ponder your mortality to live your life as if it would stop. Your only life is the most precious possession you have and it is your duty, your covenant with yourself, to make the best out of it.

Consider: You make the most important decisions of your life when you are too young to make them. You may spend the rest of your life pinned to the career your young self chose for you. You may be living now with someone that you chose from a very different perspective. Both your partner and you are very different from your younger selves who fell in love in your past. Whatever life you now have are based on decisions you made before, be it yesterday or 25 years ago. If any of your circumstances changes, it makes sense to check if the results of the little existential scale are still holding true. Often, if you really did not pay attention to your life, you’ll find all three spheres of your life have gone south. You are in a negative place, a negative relationship and a negative life situation.

Why spend any portion of your only life in situations, places, or with people that are not good for you?

Granted it is easier to realize that something is not good for you than actually leave it. But take a step back: how did you get to be in this situation, in this place or with this person? What were your considerations? What informed your decision? You may realize that you chose a career, or a spouse with less consideration than you accord to choosing an Internet provider. Perhaps your casual attitude to life changing decisions was based on the illusion that you can always go for another life? That given enough time every action can be undone. The question of course is do you have enough time to wait?

Most of us do not get trapped in the wrong life. We choose it and by doing nothing to change it we actually decide to stay in negativity. It is akin to being passive- aggressive with your own self.

I believe that your only life deserve to be taken as such – one journey, with one ending. Once you get off that is it. Your life is dispensable to your contemporaries, to say nothing of the universe in its unfathomable dimensions. You only really matter to your parents and if, fortunately for them, they die before you, no one else would care about you more than you care about yourself. The loyal, ever present you, is all that separates you from hurtling into oblivion. Your duty to yourself is your most solemn responsibility: the only duty that cannot be shared with anyone else.

Of course, you cannot be forced to care about yourself. And often, the way you mishandle and abuse yourself would not be known to anyone but you. Now that should have been enough. After all only you can realize the truth about your current condition and you are the only one that can decide to change it. Unfortunately, we are experts in lying to ourselves. So good, that we can convince ourselves that what we know about our condition is at the same token totally untrue. We do it all the time: Our casual treatment of our own life is the best testament to that.

I want to clarify something important: There is nothing wrong with lying to yourself. You are allowed to tell yourself whatever you want and change your mind as often as you want. Lying to yourself is mostly in the category of “white lies”: saying something untrue in order to comfort. In the complexity of the inner world truth is not always a virtue. But in believing your own white lies you may lose sight of what is positive or negative for you. You may convince yourself that this place, this person, this situation, is not so bad or that it is merely neutral. You may convince yourself that you have plenty of time to repeat your mistakes, stay indefinitely in conditions that are negative for you, sacrifice your happiness for others; in short, abdicate your responsibility for your own life.

This is, as I see it, the dilemma with the immortality white lie: Lying to yourself that you are immortal is absolutely a good thing. It makes the inevitable death less frightening. But behaving as if you are immortal can get you stuck in a painful and depleting situation, a negative environment or an abusive partner for much longer than you should have allowed and agreed to.

So in addition to the little existential scale above, you can ask yourself the following hypothetical question: suppose this was my only life would I have___________________? (You fill in the blanks)

You see where this leads: you may have made some irreversible mistakes. Statements like “I could have”, ”I should have”, are often deluged by a wave of self- recrimination. This way of thinking is unnecessary: in my work, I try to help people not to break down under the scary weight of irreversible mistakes. We all make them. But some of us are more able to find a way around them; while others waste their time (their only life), either paralyzed or desperately trying to undo what cannot be undone.

Irreversible mistakes cannot be undone. The more you miscalculated your life, the harder it is to ponder existential questions. It may be so agonizing as to prevent you from any attempt to evaluate your current situation. Indeed, perpetual state of denial is a sensible, if very flawed, strategy, if you are helpless against the results of your own decisions. But your life is not merely the sum of your mistakes and bad decisions. Many of us become so focused on the mistake and its results; you may spend a lifetime “trying to fix my mistakes in order to be happy”. That futile activity perpetuates the mistake, and fixates your gaze in the wrong direction: Correcting your irreparable missteps is not a prerequisite to contentment. In your inner world cause and effect are meaningless and that is what counts.

My philosophy of life is based on one basic principle: You are not immortal and this is your only life. Furthermore, if this pretty irrefutable fact informs your life, other useful concepts would emerge: Your importance is relative: the larger the lens, in terms of distance and time, the less significant you become. The only place you reign supreme is your inner world. This world is born and dies with you and this is the place where your importance is absolute. It makes little sense to ignore your inner world or to introduce into it the rules and regulations that you use in your everyday interactions with the “outside world”. You are in charge of your inner world and you should be setting the rules there. The most critical responsibilities to yourself cannot be shared with anyone else, no matter how close and well intentioned. Investing your time in repairing the irreparable, undoing what cannot be undone, and tolerating abuse in any way shape or form, is a betrayal of your only life.

You may say, I realize that I spend a large portion of my life with people, in places and situations that have negative effect on my life and me. How can I suddenly change it? I am too stuck.

In future blogs I will offer simple and doable strategies to setting the rules and regulations for your inner world, taking the lead on responsibilities to yourself that cannot be shared, and moving away from negativity. You may be surprised at how easy it is to engage in those activities. But the first step is measuring your present situation by an existential scale, and thinking you are immortal but acting and behaving as if this is your only life. Because it is!

Summer is upon us and with it the images of sprawling, manicured lawns and the lush greenery of the countryside. I am reminded of an old question: How do the British manage to have such amazing lawns? The answer is: they do everything needed to start a lawn, they meticulously take care of it, then they wait 400 years and Voila!

Meeting a soul mate is based on the same principle; you meet someone, you cement your bond, you consistently cultivate your relationship through thick and thin, and after some years, voila! You are soul mates.

Now seriously, I think it is hopelessly romantic (which is not bad) and often bitterly disappointing (which it is), to assume that a complete stranger, whom you meet for the first time, can perchance be a soul mate to you. In other words, the chances are slim to none that you can meet your soul mate. Your partner and you can become soul mates but it takes some planning and dedication.

We tend to trust the complex emotions we feel toward our “chosen one” as a sign that this is the right person. Yet, these emotions are not very reliable when identifying a potential soul mate; no love, however intense, can be trusted to continue growing – or even remain strong – without consistent investment. Neglected relationships are doomed to fail – just look around you! We often behave as if our own bond is a self-generating, everlasting mutual fondness. Sadly the reality is quite the opposite: most ignored and unattended relationship, fizzle from volcanic fire to a flimsy candle in the wind, feebly flickering in and out.

You may ask yourself: what is so great about having, and being, a soul mate? The answer is simple; falling in love is the spark that starts a relationship. When that sparks dims, your couple dynamics need to switch from temporary to (hopefully) permanent. The permanent bond is based on a different foundation. After a certain time together, whatever bonded you at the beginning of the relationship does not hold strong any longer. At that point, the risk is that your connection as a couple would devolve into a routine, vague, infrequent feelings of kinship, and the fear of change.

Let me explain: At the beginning of a relationship we all have many fantasies about the future and very few memories together. With time, the weight of our memories outweighs the levity of future fantasies. If you were not attentive to your relationship, the memories can be so painful and distancing, as to burden down any possibility of ever soaring again.

Say you look at your partner, some time after you cemented your relationship, and realize with the first ping of horror that you may have made a fatal mistake: This person is not your soul mate!

I suggest you can relax. Of course he or she is not your soul mate, or “the only one”, or “love of your life” or even your best friend. It is impossible!

You are not a marathoner (yet!) after the first mile of the run. And you cannot even aspire to run a marathon just because you decided to: You need to put in some lengthy and hard slog. Similarly, relationships are among the few aspects of life necessitating consistent work over time to reach and sustain a desirable result. Exercise does come to mind as a metaphor since no mater what level of fitness you reach, you can never rest on your laurels and stop working out. You will lose in a short time what you had built over years.

You may say, “I have settled into second rate, passionless and loveless relationship and I have no problem with it”. That is obviously your choice. And yet, the emotional and physical price of dealing with pent-up aggression and crushing loneliness, when trapped in neglected relationship, is much higher than the investment entailed in creating true soul mates relationship.

So by now we know that you do not meet a soul mate – you create one!

But what exactly is it? In a few words soul mates relationship can be defined as a perpetual and growing love. Let me define what I mean by love. After all there are as many types of love as there are days in one’s life. We love many things: chocolate, our children, a vacation on a beach, the sound of favorite music, a drive in a country road. What we love is constantly changing: The charming resort is not as magical on second visit; Yesteryear’s passionate love is todays forgotten shadow. We may discover that except for our addictions and our children, our ability to love has no permanency over time.

Soul mate is a very special case of love. At its best it is almost akin to the love we feel to our children. Almost, since the love we have for our children, is unconditional and the love for a soul mate is not. It is conditional on the unbroken avowal of the special, unique status that binds both lovers. Paying attention to your relationship can transform them from a bond to a covenant.

You deserve it.

Let’s examine the two most common scenarios: one for those who are searching for a long-term partner but have not found one yet. And the other, for those who are in long-term relationship and would like to improve them to become the covenant they should be.

Our western contemporary culture leaves the search for a mate and the ultimate choice to bond, to the future couple. That freedom to choose a partner is no doubt a great improvement over the arranged marriage practice of past centuries, but it has created new problems. Those who have difficulty deciding can spend years being unsure, and those who tend to be impulsive, might hastily commit to the wrong person. But one basic issue is so universal as to influence every consideration: the preoccupation with finding the perfect person. Even if you logically know that a perfect match is an unfortunate myth, you still secretly hope to find one. If you believe, as I do, that most romantic partnership can be worked into a covenant, then your decision making is likely to be different from the prevailing “gut feeling” considerations that informs current choice of mate in our culture. Instead you might look for someone who would be committed to growing the relationship. Someone, with whom you can partner to avert the fizzling of your bond once the original emotions, burdened by reality, are incapable of carrying you through.

But what do you do if you are already in the “relationship fizzle” phase? You entered your lifelong partnership based on intense and shared fantasy. You promised yourselves that you would “live happily ever after”. Now you trace a sense of bitterness, connection fatigue, and growing estrangement. What can you do?

How you fix it is dependent upon the two of you. You may have crossed already the point of no return, and your relationship is irreversibly broken. The weight of bad memories – the resentment – returns you to the point where you met: two strangers. Only now the past is so heavy as to prevent any renewed closeness and fantasies are not about being together but about breaking up. You must do something. Everything can be improved given one condition: your partner must be willing to do something as well. Otherwise, there is no reason to stay together and spend the precious rest of your life with someone who increasingly dislikes you and vice versa. I do not wish to be flippant about the premise of breaking up. I know how hard it is. But it is the difficulty inherent in breaking up that paralyzes a couple from acting upon it. So the only honest conclusion is: either improve your relationship or consider separation. Staying passively in unattended relationship is often a recipe for growing unhappiness. Whatever the future beckons, is only an illusion. The past may be a repository of growing disappointments. The present is the only time to decide and act on your needs.

If it is time for action I always recommend couple’s therapy. But even more essential is the “couple’s therapy” with yourself. Unless you repair the relationship with yourself, there would always be a voice, telling you from the depth of self loathing, that you do not deserve any better. Disrespect for your own life, provides but a shaky foundation for meaningful relationship with others.

Don’t give up on yourself. Don’t give up on your chance to be in positive and growing relationship.

Remember: you do not meet your soul mate. You create it.

Sleep is a mysterious activity that most don’t consider an activity at all. It is essential to life – several days of total sleep deprivation can result in death – but most of us do not encounter people who died from sleep deprivation. We do encounter every day, perhaps while looking at the mirror, people who are chronically sleep deprived. Our cavalier attitude to sleep, as if optional, is truly inexplicable, if we consider its centrality to our quality of life.

Most of us have become so “adjusted” to chronic sleep deprivation, it almost seems “normal”.

You may be aware that you are groggy, but the serious disruption to your memory, concentration and attention – the consequences of chronic sleep deprivation- might be imperceptible to you. Chronic sleep insufficiency also induces stress biomarkers, interferes with weight and hormonal regulation, and results in irritability, anxiety and depression. Those are all heavy-duty issues. In fact, we are so sensitive to lack of sleep that even a reduction of one and a half hour, for only one night, has been demonstrated to decrease our cognitive effectiveness by 30 percent.

You may treat quality of life essentials, i.e., exercise and good nutrition, as optional but we all must sleep. No one ever succeeded a voluntary sleep deprivation. It is impossible. But why can we not sleep more efficiently? Why do we have to sleep so many hours? We have totally revolutionized the waking hours, inventing one timesaver after the other, thereby making two thirds of our life increasingly efficient. Why can the other third not be revolutionized? Why can we not enjoy condensed sleep of 2 instead of 7 hours a day?

We still know little about the subjective experience of sleep. We can observe the dreaming person, but much like the experience of death, no one has ever been able to give a first hand account.

Curtailing sleep makes the same sense as curtailing the intake of water. Sleep cannot be rationed and needs to be played out in a complex repetitive and mysterious ritual: The sleep cycle, the REM vs. Non REM sleep, deep sleep and light one, dreams and amnesia. Much like the steepest depth of the oceans and the far reaches of galaxies, we have but recently become slightly acquainted with the mystery of sleep. What do we know for sure? We know that sleep is essential to our life. We know that on the average adults need to sleep at least 7 hours per day. We know that sleep is tightly regulated by our circadian rhythm. We are also familiar with the notion of Sleep Architecture – the rhythmic five phases of sleep that we usually pass through: stages 1, 2, 3, 4, and REM (rapid eye movement) sleep. Whether we sleep too little by choice or due to a sleep disorder, most of us make the same mistakes when retiring to sleep. The essentials of sleep hygiene are widely known and often reviewed. For a refresher, here are two links to sites that I find to be clear and helpful: The University of Maryland Sleep Center, and the Cleveland Clinic Sleep Disorder Center

But the environment of our sleep, even if carefully and attentively controlled, is secondary to the effects of our circadian rhythm on the quality of sleep. The circadian rhythm in turn, is dependent almost exclusively on the degree of light (or darkness) that gets into our eyes. And it is no wonder: One of the most reliably recurring phenomena on planet earth is the gradual daily alteration from darkness the brightness as the nights alternate eternally with days. Our biological clock (and that of many animals and plants) has evolved to correspond to changes of light in 24 hours cycles. The hormone melatonin, secreted from the pineal gland in the brain in response to the diminishing light of dusk, is essential for our ability to sleep. As the light grows dimmer the melatonin level increases and it signals to the brain that it is time to sleep. The alternating states of sleep and wakefulness are fundamental to the rhythm of all our biological activities: The efficient and tightly choreographed dance of life.

This harmonious adaptation to life on earth has been seriously interrupted by the advent of modern technology. Almost every aspect of technological innovation is aimed at overcoming the traditional relationship between our biology and the environment. While modern technology has made our lives easier in many ways, it has been advancing at a pace that exceeds our evolutionary adaptation. This growing discrepancy between our natural rhythms and the expansion of our abilities through modern technology, presents a survival challenge to all of us. Much like the struggle to preserve our planets natural environmental rhythm, we must pay attention to our personal one. In a way, our ancient biological clock is groaning under the strain of keeping up with technological advancement.

Nowhere is it more obvious and immediate as with the regulation of sleep. Until the introduction of artificial lighting, the sun was the major source of light, and humans spent their evenings in relative darkness. Now, as soon as day light dims, we are deluged by artificial light. Daylight is artificially extended to no end and even when we retire to bed we continue to be surrounded by numerous light emitting fixtures: No wonder then, our pineal gland is utterly confused. When should the melatonin surge occur? Where is the once dependable transition from day to dusk to night? We all understand that our environment is sensitive to our technology and we need to be “more green”, but when it comes to sleep we need to be “less blue”. Less blue? I mean this literally. We must cue our pineal gland to secrete melatonin on time, without the darkness it has come to depend on. Two important aspects are the ingestion of melatonin capsules and elimination of blue light at night. The melatonin boost is simple. All research now points to the fact that very low dose of melatonin (the body need as little as 0.2mg to signal it is night) taken at around 9pm can have profound effect on the quality of our sleep. Some people may need more – but not much more than 0.2 mg – the drug stores are still selling 3 and 6mg capsules which is actually counterproductive as it floods the brain with a large surge of melatonin. The putative rewards of daily melatonin intake are numerous and a great body of research already exists and widely accessible on the WEB. For me it is one of the three supplements I take daily (the other ones being trans – Resveratrol and Vitamin D3). I suggest you read about it and consider taking it.

Blue light presents a different problem. Blue wavelengths—which are beneficial during daylight hours because they boost attention, reaction times, and mood—seem to be the most disruptive at night. While light of any kind can suppress the secretion of melatonin, blue light does so more powerfully.The environmental push for more efficient light emitting fixtures is replacing the energy wasteful incandescent light bulbs with the very efficient fluorescent and LED bulbs. But they also tend to produce more blue light. This is a curious point (albeit increasingly common) where the personal benefit is at odds with the planetary one. Green Vs. Blue! Obviously the way to solve it is not by sacrificing the environment but by modifying our personal one. On a large scale, coating fluorescent and LED bulbs with blue wave length filter, would be a universal solution whose time has not come yet but is sure to be requested the more we are aware of the real and serious problem to our health.

But until then what can we personally do to limit the effect of artificial light on our Melatonin production? One way, as mentioned above, is to take melatonin supplement to try and overcome the melatonin suppression and the absence of melatonin surge.

Eliminating blue light after dusk is not simple. The best way is to stop the light, as it is about to get into the eyes. We should remember that in order for melatonin to be secreted the light has to come through the eyes. Each wavelength visible to us excites a different group of neurons according to its relative intensity. (Indeed blind people have complex difficulty with their circadian rhythm and in a way live in a perpetual “jet lag” which has only recently been identified.) Eyeglasses that block blue light (typically the lens have yellowish brown tint) are very helpful. In a way, they are to blue light what sunshades are to day light. It is a bit awkward, and most people would be reluctant to wear it outdoors – who knows, perhaps one day it would become fashionable? Wearing the shades at home works quite well and from my experience it is not as cumbersome as I had assumed. Another way, which has other advantages, is to eliminate screen lights from the bedroom. Computers, phones, Ipads and TV sets, emit blue light (to say nothing of how disruptive to sleep the content is). Software and apps that filter blue light from gadgets are increasingly available. Also filters that physically block the glare can be applied to your gadgets. Needless to say, part of good sleep hygiene is leaving the phones and other handhelds, computers and television outside the bedroom.

Of course not all people are casual about their sleep. You may suffer from insomnia and other sleep disorders and would have loved to sleep longer but can’t. What should you do if despite a good evaluation and correction of your sleep hygiene, elimination of medical conditions that can cause insomnia, and taking care of your anxiety and stress, you still cannot fall asleep or stay asleep for the entire night? This is when pharmacological sleep aids should be considered; there are certain conditions, at certain times in life, which merit sleep medications. Prescribing sleep medication entails many considerations, including the type of insomnia, the gender and age of the patient, possible interactions with other medications or diet, and underlying health issues. Considering prescribed sleeping pills, what kind and for how long, merits a separate write up. However, the most salient and irrefutable fact regarding sleeping medications is that they cannot circumvent the issues noted above more than vitamin supplements are a good substitute for eating fruits and vegetables. It is at best a paltry imitation of good sleep and cannot replace the attention to our biological rhythm and the centrality of melatonin and light to its equilibrium. Simply put, swallowing a sleeping pill cannot cheat the brain into considering it a “goodnight sleep”. The disruption caused by sleeping aids to the sleep architecture, invariably renders them a temporary solution, one that cannot be a replacement for “natural” sleep. It is my strong recommendation that you discuss with your physician the option of taking low dose melatonin and evaluate all aspects of your sleep hygiene.

I understand that most do not want to waste their life sleeping. Yet given that the quantity and quality of sleep is essential to your ability to function during the waking hours, and has enormous consequences to your health and wellbeing throughout life, you would not want to waste your daily restoration (literally!!) on second rate, poor quality and insufficient sleep.

Chapter 1. Psychiatric medication

Recently I watched a National Geographic documentary: Stress – Portrait of a Killer. In it, the brilliant Stanford neuroscientist, Robert Sapolsky, compares human stress to that of Primates and other animals. Unsurprisingly, when humans and other animals experience stress, we all have similar increases of stress hormones in the blood. That is hardly a basis for a fascinating documentary. However, the catch is that we, humans, have the same level of stress hormones just by thinking about potential problems, as a zebra would when it flees for its life from a pride of lions. Moreover, if the zebra (or any other animal in danger) survives the predators, the hormone levels return within 10 min to the pre-stress baseline. Without “reflecting on what happened”, the Zebra continues grazing with the herd, unconcerned and calm. We are the only beings that are stressed by our imagination rather than a real physical danger. We tend to worry about the future, which invariably exists only in our imagination. If you worry about your plane ride in the summer, how can you deal with it?

When the zebra identifies a danger, it runs for its life. It can DO something about it. We, on the other hands, are helpless against most of our worries. We can do nothing about them since they do not exist, at least not yet, not now. Surely preparing for a predicted hurricane gives one a sense of mastery. But how can you deal with the thought that you will never be happy again, or win the competition, or get the job, or the love, or the place, you hope for. How can you protect against a fear of flying, or failure, or of old age, or death? We are aware of many potential problems, some real but most imaginary and totally out of our control. Indeed, the ability to think in symbols, to imagine – exclusive to humans being – is our mixed blessing. Among all living things, only humans have developed the ability to think about the past and imagine the future in the sophisticated form we call consciousness. Our young cognitive apparatus – approx. 100 thousand years old – is superimposed on an ancient emotional system (about 100 million years). It seems as if our emotions are unable to distinguish between the concrete, reality-based present tense, and the imaginary, timeless inner mental world. And so, our emotions react to some imaginary future danger, in the same way it does to a real, concrete and current threat to our life.

People who are constantly preoccupied with “what ifs”, and “should haves”, invariably live stressful life. The Stress hormones (adrenalin and glucocorticoids), released in the body when we worry about something, cost a huge and increasingly devastating price to our health. These hormones are meant for use in times of danger. They shut down many “unnecessary” systems and activate in full throttle those necessary to fight for survival. The toll of fight and flight on the body is tremendous, and can last only a short period without inflicting damage. In nature, whether you flee to safety or are killed is usually decided in a matter of minutes. The mammal body was not made for extended period of mortal danger. But when the danger exists in your mind, there is no obvious or expeditious resolution. You can spend years worrying about issues that never get fully resolved (are you good enough? will you develop cancer? is there life after death? etc). Additionally, you may be overbooked, overworked, overcommitted, rushing through multi tasks and racing against your own life. Stress may become such a part of your life that you do not even notice how stressful your life is and how much unnecessary pressure you add to it. But your body does not forget. We now understand the damage down to the sub cellular level. I highly recommend watching the documentary mentioned above – It should serve as a wake up call for all of us.

Some stress is unavoidable. If you care for a sick or disabled family member, struggle with a chronic illness, or deal with a loss of a loved one you would inevitably be stressed about it. On many occasions, telling you to “take it easy” is not more than a cruel insensitive remark. I never admonish anyone, myself included, for feeling stressed. It is only frustrating, and adds another layer of stress – you become stressed about being stressed. But the effects of stress are so perilous, it behooves an honest discussion about the ways to reduce it. During the next few months, I will periodically publish installments on how to reduce and limit the sources of stress in your life. Today I will focus on the role of medications in stress reduction. While I do not advocate medications as the first line of treatment of stress, I want to make clear my favorable approach to judicious, careful and targeted use of psychiatric medications in the treatment of chronic stress.

We have complex love/hate relationship with psychiatric medications. They are the most prescribed in the world and perhaps the most controversial. Even those who suffer from chronic psychiatric conditions are made to feel guilty for taking them. I agree that many people are prescribed medications unnecessarily, in psychiatry and otherwise. But in my practice, I usually encounter the opposite: people who could benefit tremendously from medications and are reluctant to take it. Some fear their brain or personality would change, some see it as admission of weakness and defeat, as we are expected to “get out of it” on our own. I will soon address those biases. But first, what kind of psychiatric medications are helpful in chronic stress, what do they do, and who should consider them? In my opinion (and this is the community standard) two groups of psychiatric medications are well suited to the treatment of chronic stress: The anti anxiety drugs (in particular benzodiazepines e.g., Valium, Ativan and Klonopin) and the SSRI’s (such as Zoloft, Paxil and Prozac). While the former group is not recommended for long-term use due to its habit-forming properties, the SSRI’s can be safely taken for prolonged periods.

Let us consider each group separately although they do have some overlapping effects:

The anxiolytics: In many ways, anxiety is the psychological equivalent of physical pain. With its myriad symptoms, both physical (e.g., palpitation, dizziness, dry mouth, tremulousness etc.) and mental (difficulties in concentration, fear and dread sensations, being “spaced out”, etc) anxiety can be very debilitating and painful. It is important to distinguish anxiety from stress: Stress is the low-grade physical and emotional tension that many feel on a regular basis. While many of the anxiety and stress symptoms are similar in their origin (a heightened activity of the sympathetic nervous system) stress is more subtle and diffused. The symptoms of stress (such as changes in blood pressure, indigestion and fatigue) are insidious and cause a gradual “wear and tear” rather than the paralyzing picture of anxiety. Most of us get so used to living with stress as to make it almost unnoticeable. Anxiety on the other hand, is usually acute, in response to something concrete, and tends to disrupt one’s normal course of life.

Anti anxiety medications are very effective, have a rapid onset and wash out of the body relatively quickly. They are recommended as adjunct to treatment of psychiatric conditions most of which have anxiety as part of the symptom picture. But even at the absence of any psychiatric disorder, when anxiety appears in response to some life’s adversity, anti anxiety medications are effective and safe. The decision to take anxiolytics for random anxiety is not medical but rather a philosophical one: It is akin to treatment of random headaches. Some people refuse to take medications against headache: while a questionable practice (recent scientific evidence demonstrates health benefit from treating headaches with analgesics) it is really up to them to decide. Most headaches are benign, short lived and if one chooses to suffer rather than take a Tylenol, it is his/her own decision. Similarly, if a person chooses not to take an anxiolytic and is willing to tolerate the anxiety, there is nothing wrong with it. Perhaps the only difference between the treatment of headaches and anxiety is that medications against headaches are over the counter, while medications against anxiety require prescription. It is a good thing: unscrupulous and unsupervised intake of anxiolytics can quickly get out of control and may lead to addiction. Yet, the administration of anxiolytics under a supervision of a psychiatrist, is safe, and can help a person get through a difficult period in life in an easier, more manageable way.

In summary, anxiolytics belong to the group of psychiatric medication that need not be restricted to psychiatric disorders. They have a role – much like analgesics – in helping reduce pain and suffering, provided they are monitored and supervised by a psychiatrist or a knowledgeable family practitioner. Once an absence of any underlying medical condition (e.g., thyroid hormone dysfunction) is established, there is no downside to using them. In fact, when one considers the physical and mental deleterious effects of anxiety and the great personal suffering, it makes sense to use them more liberally.

What about SSRI’s?

The use of anxiolytics should not be that controversial since they provide a quick relief from a painful condition. SSRI’s, on the other hand present a much more complicated decision when prescribed at the absence of a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. While I believe they have a clear beneficial role, I appreciate the controversy and would concede that those opposed to it (especially to the wide unsupervised use) have a valid point.

First, why do I support (and use) SSRI’s for people without a defined psychiatric disorder? For one simple reason: They are a great aid to psychotherapy. Historically, SSRI’s were developed as antidepressants. With time, their anti-obsession and anti-anxiety properties were discovered and put to good use in those who suffer from OCD (Obsessive Compulsive Disorder) and panic disorder. They were also found useful in PTSD, eating disorders and social anxiety among others. But they have another, related attribute that I find extremely compelling in my everyday practice: They make it possible for you to “Take a vacation from yourself”.

What does “vacation from yourself” mean? Can you truly take a vacation from your own self?

Obviously not! Most psychiatric treatment is based on the fact, that you are forever “stuck” with yourself. But you can take a metaphoric vacation from one aspect of your existence, namely, the intrusive chatter in your brain. We all experience intrusive chatter: think about a time in your life when you were preoccupied by thoughts you did not want to have. Remember the night before the big exam? You may have said to yourself, “I’d better get a good night sleep and not think about it”. And yet, no matter how hard you try to distract yourself from thinking about the exam, you still find yourself at 3am, exhausted, unable to sleep, and totally consumed by anxious thoughts. Chronic stress sufferers have an “intrusive chatter” most of the time even without a specific trigger. The intrusive content might be self-deprecating, self-defeating, self-loathing or merely pessimistic, in short all types of negative and unhelpful thoughts. While the underlying mechanism is probably the same for constant chatter and obsessional thinking of OCD (that is why SSRI’s are helpful in both) there are substantial differences: OCD thoughts are very fixed, concrete and are usually perceived as irrational by the sufferer. In “constant chatter” the thoughts are poorly formed, fleeting and without any real sense of irrationality. The thoughts might be “I cannot do it” or “I need to lose weight” or something similar. While not illogical, they are unhelpful, distracting and often very discouraging. Constant chatter does not amount to the strong interference and prominence of intrusive thoughts as in OCD. Rather, constant chatter is like white noise: it is always in the background and increases in inverse proportion to the level of distraction around you: The quieter your environment the more intrusive it becomes. And so constant chatter is at its peak when you are trying to rest, sleep, read, or concentrate on any type of mental activity.

One of the activities most disrupted by constant chatter is psychotherapy. By design, most of the psychotherapeutic “work” is done internally. As you concentrate on issues you would like to change while trying to focus on your inner world, the constant chatter intensifies and disrupts your connection with yourself. The annoying, repetitive and negative thoughts that flutter in your mind prevent you from attending to your feelings, since you cannot affect any distance from yourself. That is when SSRI’s come in handy: They are invariably able to stop the constant inner chatter. Once effective (and it can take months before it takes effect) you find yourself, perhaps for the first time in your life, being able to sit and think about nothing in particular and better yet, turn off at will the annoying intrusive thoughts that reverberate unwanted in your mind. Taking a vacation from yourself does not mean (as many people believe) taking a vacation from your feelings. Many consider SSRI’s a “feel good” medication, believing it is meant to numb emotional response to everyday life. Nothing can be further from the truth: SSRI’s enables those who suffer from constant chatter, to choose whether they want to think about something or not. I like to describe the mechanism the SSRI’s, in a nonscientific terms, as a movable padding – positioned between one’s thoughts and feelings. Moved into position, it creates some buffer between the anxious thoughts and the anxious emotions. The chronically stressed person can, at long last, block a mental concern from igniting a vicious cycle of a cognitive/emotional storm. Conversely, the same mechanism prevents an anxious pang from exploding into a cascade of concerns.

In summary, SSRI’s and anxiolytics should definitely be considered as an effective way to prevent our imagination from igniting an unnecessary stress reaction. There are other proven techniques to decrease and control stress in our life. I will cover them over the next few months. Ideally, our stress reaction should return to the role nature intended; to sharpens our mind and reflexes in the presence of a real present danger or concern. By “abusing” that rapid intervention system for petty or imaginary concerns, we deplete our emotional resources and reserves. We must learn how to stop our futile, self-destructive struggle with our imaginary demons.

I cannot think of a better Spring cleaning plan.

Remember Bo Didley’s song “Who Do You Love”? I think it is a good question to ask yourself this Valentine’s day. Seriously, whom exactly do you love? And what do you mean by love?

I just finished reading a book (“Mind, Modernity and Madness”, by Liah Greenfeld). The book’s main focus is on culture as a causal element in mental illness. Accordingly, it starts the discussion by describing the progress of early humans from developing the capacity for language, to articulating signs and finally to articulating symbols – i.e., something that stands for or represents something else. It is always fascinating to consider the context of psychological evolution. We can think of anything we want and make up any story in our mind: be it in the distant past or the immediate future, in places we have never seen and with people we would never meet. Being liberated from the concrete and acquiring the freedom of the abstract, offers boundless possibilities.

Imagination, fantasy life, daydreaming and the ability to think in symbols offers a rich matrix for creating an “as if reality” inside our mental world. Which brings me to the avatar: Obviously, our perception of reality is very subjective. The glass is half full or half empty, the picture is dark or bright: our mood colors our thoughts and our thoughts in turn affect our mood. No matter how factually based, eventually almost everything in our life becomes relative and dependent on how we choose to see it.

Nowhere is it more poignant than in our choice of a romantic partner. Ask yourself: How do you relate to your partner when he or she is not with you physically? Or better yet whom do you relate to? Who do you miss? When your partner is with you, his or her physical existence supersedes your fantasy about them in your inner world, but when you are apart – whether at work, traveling, going to classes etc – you interact with them in your mind. Obviously, you cannot bring the actual person into your inner world, so you create a representation of your romantic partner in your mind. I call this representation, the avatar.

Often the avatar is very close to the real person it represents in your mind. But at times, they have almost nothing in common. You can have a host of interactions with the avatar that are very different from the ones you have with the real person. In fact, you may have a whole emotional experience with the imaginary figure: you can have a fight with the avatar, seduce the avatar, lecture the avatar, love the avatar or scold it; but it is the avatar, not the real person, and you might be surprised to see how far you have gone with your mind’s creation. It is common to have leftover feelings from an imaginary, inner altercation, much like the odd feeling that lingers after a difficult dream. You know it is your imagination, but your emotional device continues to create “Phantom feelings”.

Valentine’s day is a good occasion to ask yourself: Whom do you love? Is it your romantic partner’s avatar? How close is the avatar to the real person? Does the avatar possess some idealized traits the real person doesn’t’? Does “spending time” with the avatar seem better and more pleasurable?

You may discover that you indeed have a relationship with two entities: your partner and his or her avatar. Even if merely a figment of your imagination, the avatar influences your relationship with your real partner. Evolutionary speaking, our emotions are so ancient compared to our cognitive abilities, that we are often unable to separate our imagination from reality. (Try this: Think of a something you like to eat when you are hungry and your mouth would literally start watering. The food is not around, you do not see it, smell it taste it. You just imagined it. Still your body reacts to the fantasy as if it was real).

After some time together, you may find that the boundaries between the real person and the avatar become blurred. If it is more pleasurable to be with the imaginary partner than with the real person, you will start overlooking certain aspects of your relationship, idealize or devalue others, and increasingly “live” with the avatar at the exclusion of the real living breathing partner.

Fantasy is wonderful as a sweetener of life. Our childhood fantasies – those immensely pleasurable, sweet daydreams – are gone, tossed away forever by the rush of life. They are gradually replaced by “realistic” fantasies. These grown up fantasies can still bring us pleasure and sweeten our life. But they often create an alternative reality. This is precarious since we start to compare our lives to our fantasy about them. And since no reality is as good as its corresponding fantasy, they can interfere with our ability to enjoy our real life.

The question “who do you love?” is indeed quite pertinent to your relationship. Valentine’s day, the ultimate romantic vortex, is a good time to evaluate it. Do you love the real, flesh and blood person or his/her idealized imaginary version? If the avatar pops up, its time to turn back to your original love, the person with whom you chose to spend at least part of the journey, if not all of it, together.

Much of my free time I spend with my geniuses. Quiet and ready they weigh down my bookshelves. Borges, Nietzsche, de Saint Exupery, scores of geniuses, all are there, all are mine. Above them all, always towering in my supplicant mind stands delicate and tall my ultimate advisor: Franz Kafka. In a letter to Oskar Pollak, on November 8, 1903, he wrote:

“We are as forlorn as children lost in the woods. When you stand in front of me and look at me, what do you know of the griefs that are in me and what do I know of yours. And if I were to cast myself down before you and weep and tell you, what more would you know about me than you know about Hell when someone tells you it is hot and dreadful? For that reason alone we human beings ought to stand before one another as reverently, as reflectively, as lovingly, as we would before the entrance to Hell”.

I cannot think of a more disheartening statement for a psychiatrist. I read his words when I forged my first hesitant steps into this formidable field. I literally agonized over the thought: what if Kafka is right? What if I set myself for a futile chase of the eternally inaccessible? As a physician, I am totally prepared to stand before the other reverently and lovingly. I understand the hellish nature of emotional pain. But will you never be able to explain to me your inner world?

Years into my practice, I have understood the lesson of my great genius teacher: we are inherently incapable of expressing to the other what takes place in our inner world. As a psychiatrist, I cannot expect you, my patient, to explain to me your inner world, much like you cannot describe what is going on in your spleen or thyroid. You can explain to me your symptoms, but as Kafka said, all I know is that hell is hot and scary. That is not enough to be profoundly effective. In order to understand your inner world I have to visit there. I have to imagine your life and experiences as they appear to you. In other words, instead of “putting myself in your shoes,” I have to become the other even if for a split second – and suddenly everything is so clear.

It took me a long time to learn how to lose my judgment at each psychiatric encounter. Like Yoga or any other spiritual discipline, it is a long learning curve and one never masters the technique to full perfection. I certainly am often reminded of my limitations. And, as opposed to Yoga, no “muscle memory” is permitted. We may be predictable in the outside world, among our fellow humans, but inside our most intimate sphere, our experience is unlike others’. And so, despite the years of experience, I often need to exert myself intellectually and spiritually with every person as if they were my first. But once the moment of clarity occurs, when the glow of understanding illuminates another’s inner world, it is forever revealed in all its intricacies.

I have been thinking about communication this week as I was scheduled to give one of my Men(ual) seminars. I created the workshop some years ago, responding to my work with couples. Typically, a focus of a couple’s work is improvement of communication between the two. And yet, at times I realized that even with “simultaneous translation” the man and woman sitting with me are unable to understand each other. They want to listen to each other. They are attentive to each other. They love each other, and want their relationship to work. But they do not “get” what the other is trying to explain.

This is the juncture where I reach for “my Kafka”. Is there a way for someone to express their deep emotional needs, even when their words betray them?

I have developed my Kafka method to find alternatives to dialogue, alternatives to verbal communication, if you may.

Try this:

Together with your partner, identify an issue that is very important to you even if it seems insignificant to your partner. We all have those “hang-ups” – pet peeves that can drive us mad even if we ourselves can recognize that “it is not a big deal”.

True, it is not a big deal in the outside world, but it is a big deal in our intimate, deeply veiled, inner world. Why? There are as many possibilities as there are people and hang-ups. And, when working on your relationship with your partner, you need to focus on the dynamic and understanding between the two of you. Disagreement on “small things” is in fact one of the most destructive and erosive force in marriage. People can torture themselves and their partners over the most inane issues. And often it takes the form of a “ritualistic dance” where the couple acts like well-rehearsed actors in a play. I assume you must have experienced it. I certainly have.

Now think of Kafka’s words. It is important to be reminded that sometimes we cannot explain the why in our heart. It is just there. And, while difficult to explain, it is important to you nonetheless. And yes, you can ask your partner (especially your partner) to accept that importance without you having to explain. (And perhaps if both of you stop bickering about it you would be able to become more flexible yourself.)

Some behaviors, or feelings, or needs, might be impossible to explain. But they are there, and very powerful. My Kafka method can help us accept the fact that we may never get an answer why. Once we overcome this hurdle, suddenly the road to a loving partnership becomes clearer. Simple? Perhaps. But it is not too simple to be effective.

Truth is not necessarily a virtue when it comes to your relationship with yourself. Universal concepts such as Truth, Morals, Ethics, Rules etc, are really meant for your relationship with the others. It is very hard to apply them to your inner world. Are you allowed to lie to yourself? Can you keep a secret from yourself? Can you punish yourself for punishing yourself?

Think about it: most rules and regulations – whether written or unwritten, culturally sanctioned, or ordained from heaven – take on a very different meaning when applied to your inner world. In your relationship with your own self, most do not make sense at all.

In my work as a psychiatrist, I help others examine and create their inner rules. Often the biggest hurdle is convincing my listener that he or she is entitled to do so. We are so paralyzed by our adherence to the social rules, that we dare not abandon them at the gates to our inner world. And by dragging them inside, we violate one of the only sanctuaries we can depend upon.

Many of us spend a great deal of energy disagreeing with our own thoughts and feelings. When we say: “I should not be thinking or feeling this way”, we assume that we can control our emotions or thoughts. Yet, at most, we can control the active/external expression of our thoughts and feelings (and even that can be very taxing and often impossible).

We cannot control our thoughts and feelings. We have no easily available mechanism to do so. Our brain is so busy with the immeasurable amount of tasks it constantly performs – the vast majority we are not conscious of – that preventing it from thinking or feeling something, is futile. The most we can do is ignore the thought or the feeling and let it slip away. The unfortunate catch is that exactly the thoughts and feelings we do not want to have are the ones that stick longer in our awareness. And as each one of us knows, the harder we want to get rid of them the more stubborn and sticky they become.

And so, working to prevent unwanted thoughts, or shove them away, is not practical. The trick is not to assign value to one’s thoughts or feelings. If we do not exercise an appraisal of a thought, it cannot have a “wanted” or “unwanted” quality. This brings us back to the issue of inner rules.

Our thoughts and feelings have no inherent moral or legal value. So long as we keep them to ourselves, they do not exist in the outside world, and have no impact. Thoughts and feelings that make their way to the outside world, acquire the power to affect the others. This power is checked by our social rules lest we devolve into chaos. But the majority that floats through our mind, some lazily, some frantically, and some almost imperceptibly, those thoughts exist only for us.

Obviously some guiding principles exist for our inner world. Otherwise, it could also devolve into chaos. But they are not the same principles as the social ones. (Nor do they have to be, as you have already realized.) One of the most important principles for our inner world is authenticity. By “authenticity”, I do not mean a factual truth. “Facts” are also meaningless in the inner world. Authenticity is the ability to know when you are lying to yourself and to be able to acknowledge it. You are welcome to lie to yourself as much as you want to, so long as you are able to be authentic about it. Most of us need to learn how to do it. We are so frightened of our thoughts and feelings (and even worse; the interaction between them) that we spend time lying to ourselves about it with the hope that we would “buy the lie” and put it to rest. But we cannot fully lie to ourselves since we also know the truth. And, the bigger the lie, the more emotionally costly its maintenance becomes.

Self lies, or in psychological parlance, denial, often help us cope with unpleasant reality. And since lies, in the inner world, have no qualitative value, i.e., are not “bad” or “good” – their service should be recognized for what it is. They become a problem when we try to convince ourselves that they are not lies. The truth of course, interferes with our ability to believe in the lie. That is where authenticity comes in handy.

I will give an example: One of the most commonly encountered inner lies is that of a spouse trapped in unhappy and distant relationship. I am not talking about abusive relationship. In abusive relationship the abuser “casts a spell” on the abused and is actively promoting the lies. I am talking about the familiar slow grind of parallel lives, growing emotional distance, and low level, chronic mutual resentment. Sadly, this common condition can start quite early in relationship, peek after a decade together and continue unabated until the end of the life together. Eventually, and often later in the game, the spouse that suffers the most from the relationship ‘s poor quality, simply gives up trying. And that is a good thing: the one who gives up, does not need any longer to maintain the lie. Hence, the energy required to maintain the self -lie is freed up for other, hopefully healthier, pursuits.

If we are scared of the truth, we are unlikely to abandon the lie. Hence, we may continue on an increasingly depleting and depressing trajectory. Learning to observe the lie without having to abandon it, makes it much more possible to plunge into a trajectory of change.

To summarize:

1. The rules and morals that we apply in our dealing with the others have no real meaning in our relationship with our own self.

2. In our inner world we cannot truly lie to ourselves since deeper inside we also know the truth.

3. Some self -lies are harder to maintain than others. Some (for example denying the inevitability of our death) are becoming harder to maintain with time. But the more poignant and urgent the truth, the higher levels of energy is needed to stifle it with an inner lie.

4. Our self- lies, much like our fantasies, often serve a purpose in making our life more tolerable, or enabling us to distract ourselves from a painful reality.

5. Authenticity in our inner world, is not giving up the lie or adhering fanatically to what we know is the truth. Rather, authenticity is the ability to acknowledge the fact that we are not truthful to ourselves about something.

For myself, I have always believed in the adage “the unexamined life is not worth living”. Obviously, it is not in my purview to decide the worth of other people’s life. So I offer you a milder version: The authentic inner world makes life easier and lighter. And that is a positive gain in and off itself, isn’t it?

(what would the others think?)

Relinquishing your self definition to others. The case of “Lara”

We care deeply about what the others think of us. In fact, many of our activities are intended to affect the perceptions of those around us. While one of our most basic freedoms is to define ourselves to ourselves, many relinquish this freedom. Instead, we let the others define us and, by doing so, we give the power to others, even total strangers, to shape the way we see ourselves. This self-imposed vulnerability interferes with our emotional self -reliance and is a major contributor to the sense of insecurity so prevalent in the human experience. Insecurity is the outcome of reliance on the others for the sense of self esteem (no wonder we associate insecurity with little self esteem). Self-esteem is literally how we value ourselves. Your sense of self-esteem, when dependent on others’ opinions, is not in your possession. It is merely borrowed from the others and as such cannot be seen as self. Borrowing your self-esteem is very precarious: one day, when you do not meet the terms of the “lease” it can be taken away from you. Even the most complacent narcissists, know in their heart of hearts how fragile their position is. Ultimately the absence of a solid, independent sense of who we are renders us insecure and scared of life.

Lara came to therapy complaining of “paranoia”. “I feel very self conscious; everywhere I go I feel that people are looking at me and judging me”; she feels people think she is ugly and a “loser”. In reality, Lara, a 24-year-old graduate of prestigious masters program, is pretty and personable and does not posses any trait that can attract negative attention. She recently accepted a job offer at a prominent institution but feels so overwhelmed she in not sure that she can actually start working there. Being so hard on herself, her family and friends try reassuring her that what she feels is just her imagination. Lara is not persuaded “They are just trying to make me feel good, but I know better”. Over the years L. has restricted her social interaction, finds it hard to walk into a crowded place and despite experiences to the contrary, has a very low self-image.

Trying to understand how she views herself; it quickly becomes apparent that Lara does not know “who she really is”. When asked to describe herself, she finds it extremely difficult. She states – with little conviction – some external facts while looking uncomfortable and seeking assurance and approval. Not having a good sense of herself, Lara is very vulnerable to how other people see her. She constantly scans the others for their reactions whether real or imagined (Most probably imagined, as she is most vulnerable to random strangers on the street, who are unlikely to form any opinion either good or bad.)

If you ask “How come you are so willing to accept imagined opinions from total strangers and not the positive feedback from people who know you well?” Lara would agree: “It is weird, why do I care so much about random strangers who do not know me at all?”

Actually this is not so weird: strangers can only see the exterior, i.e., your appearance. Conversely, family and friends know you on a deeper level: your history, your personality. In reality your appearance receives little attention from people who know you well, as they are used to the way you look. When you do not know yourself you tend to view yourself like a stranger would; you see only your exterior. No wonder we give so much credence to the opinion of strangers: Being strangers to ourselves we identify with their “point of view”. Much like strangers we connect with the superficial aspects of our existence – for example our looks –rather than the deeper layers that are “unfamiliar” to us.

The price for not defining ourselves to ourselves is a shallow self -perception, that of a stranger. Constructing your self definition around the way you appear to others renders you vulnerable and insecure. (A whole industry is based on this vulnerability: since in the Western culture good looks is equated with youthful looks, those invested in their looks are forever doomed to fight a losing battle against the ravages of time, and are susceptible to any method that offers “age reversal”.

The work with Lara is focused on helping her develop a solid definition of herself. She can benefit tremendously from uncovering her authentic and consistent self-definition: This may sound straightforward, but actually it is one of the most difficult endeavors in psychiatry as we are usually terrified of facing our authentic self. However, refusing to face ourselves is akin to a child covering his eyes so the scary thing would “go away”. Whether we look or not, our own self is always here with us, and ignoring it would not make it go away. The sooner we face ourselves, authentically and courageously, the better is our chance to live at peace with ourselves. No wonder Lara needs much support as she struggles to overcome her fear: “what if I hate whom I really am? “.

In my years of work I often encountered the inner “bogey man” phenomenon. My patients being scared of discovering a fearsome – hitherto unknown- inner secret. Yet, you are very unlikely to find something in your inner world you never knew about. In actuality you do know who you are, warts and all – you just do not want to look there. Perhaps at some point in your past it was useful to distract yourself from yourself and forgo introspection. By now, alienation from yourself has become the problem even if it once was your “solution”. True: while facing your authentic self you may not like everything you see: however, you are unlikely to discover a dark secret about yourself you were truly unaware of.

Acquainting you with yourself is only the beginning of the process. Imagine returning to your childhood room: The posters you once loved seem quaint and outdated, your bed is too small, the chairs too low: it is still your room but does not meet your needs any longer. You need to reassess and examine your notions about your life: Slaughter some “sacred cows”, connect with inner instincts rather than borrowed notions. Most importantly, you need to get rid of unnecessary “garbage” you hoarded inside and were never able to sift through. Almost like “interior redesign” of your inner world. Once Lara was able to face herself, the work became increasingly rewarding for her. As she began to realize that her inner world is in fact a fascinating place, and highly worthy of her attention, her sense of self got better formed and her dependency on external definitions became greatly diminished. Lara dared for the first time in her life, to define herself for herself. !

Do you suffer from the “Borrowed dignity Syndrome? Questions to ask yourself:

1. Do I often feel that I do not know who I really am?

2. Do I constantly seek approval from the others?

3. Do I often wonder what kind of impression I make on the others?

4. Do I try to be what I think the others want me to be?

5. Am I very preoccupied by my looks, my image, and my presentation?

6. Am I very sensitive to criticism?

7. Do I get very angry and/or depressed when I feel disrespected?

8. Can I be described as having a “thin skin”?

If you answered yes to five or more of the questions you may suffer from the “Borrowed Dignity” syndrome.

Steps to reclaim your sense of identity and fully own it:

1. “A Penny for your Thoughts”: Ask yourself how you know what the others (especially strangers) think about you. The more you consider it the clearer it should become to you that unless you are a mind reader (which no one is, not even an experienced psychiatrist…) you cannot know what another person thinks. We often can tell how another person feels even if he says nothing. There are many non verbal cues we use to convey our feelings. Being sensitive to others’ emotional or nonverbal cues is a survival mechanism that helps us navigate successfully among our fellow humans. In fact, a hallmark of the autism spectrum – such as Asperger’s Disorder – is inability to “read” others’ emotions. But we cannot know what the others think. When we say we read someone’s mind, we mean his or her feelings. At times we can decipher very crude thoughts from reading one’s cues: Frowning usually means “I do not like it” and smiling broadly mean “I like it”. But this is the tip of the iceberg when we ponder the myriad of thoughts that can swirl behind a smile or a frown (not to mention that we are highly adept in masking our feelings behind a fake expression: a politician’s smile can mean no more than a professional tic).

2. Consider: most of your conscious thoughts are centered around yourself: Unless you are obsessed with someone, you do not spend that much time thinking even about people close to you not to mention total strangers. It is not a mark of self-centeredness: you can be compassionate and generous and still think primarily about yourself. We need to think about ourselves since we operate this complex machine in space and time: imagine a pilot or a driver focusing mostly about other planes or vehicles: you would not want to be driven or piloted by them. In that context, preoccupying yourself about what the others are thinking about you is a waste of your energy. I am not suggesting you should not care; it’s that they simply do not think about you – they think about themselves!

3. Consider: How much time do you devote into thinking about random strangers on the street? When you see someone unusual, strikingly beautiful, or shockingly eccentric how long does their image stay with you? Unless they do something extraordinary to you or your child (which is thankfully very rare) you don’t remember them even a day later. If that is the case with striking stranger, regular ones may not even register in your short time memory. That is exactly the way others see you. It may be humbling ( or even distressing) to think that the rest do not really care about you. But it is the truth nonetheless. Human behavior is governed by predictability. We operate according to expected norms in order not to keep the rest guessing about our next move. That is why most of us are trying to attract the least attention as we are passing by random strangers. In other words, the others are not really thinking or judging you one way or the other. Being hypersensitive to what the others think about you is really the outcome of not knowing who you are and seeking this knowledge from the others. In truth they are not thinking about you at all and even if they were there is no way for you to know what they think. It is you, attributing to them those thoughts, and not their own. By allowing others to define you for yourself all you do is project your insecurities upon them. Unless you define yourself to yourself you would continue projecting your insecurities unto the casual observer- thereby getting an imaginary “proof” to your perceived deficiencies.

4. Decide to break out of this negative feedback loop: be truly self-conscious: i.e., think about yourself. Define for your self who you are in any number of areas. You may not like what you find which is probably one of the reasons you chose not to do it in the first place. But at least, it would be an authentic assessment of yourself. Frankly, allowing the others to define you was definitely not conducive to your self image. The more you own your sense of self, the less susceptible you would be to the others’ “impressions” of you.

Thinking back at your childhood, you may realize that a lot of time was spent instructing you how to get along with the others. And yet, surprisingly little attention was paid to how you get along with yourself. It is not so strange: in order to be a member of any community or society you need to learn how to submit your personal will to the communal one. Otherwise you become “asocial” and unwelcome. But if you torture yourself , no matter how harshly, you can still be a highly functioning member of any society. Frankly, no one truly cares if you criticize yourself. Especially if like most of us you do it in the isolation of your inner world.

I called the following TIIPS “Making peace with yourself”. Indeed, in my decades of psychiatric practice befriending oneself is probably the most universal goal of any human intervention. It is possible, and easier to achieve than is commonly believed. You do not need to spend 10 years untangling 10 years of self-hostility. The ratio is in your favor and the progress is exponential once you get ”the hang of it”!

The “Martyr” Syndrome: Sacrificing your needs for the Communal ones. The case of “Marcia”

Marcia is a 46 year old, mother of three. When we first met, Marcia described herself as being selflessly dedicated to her family. She said it gives her great joy to cater to her family’s needs and she feels no need to make demands on her husband and children. She said she does not need any reward; her sole gratification is to see her family happy. However, as is often revealed in therapy, beneath her seemingly cheerful facade, Marcia is actually bitter and depressed: By convincing her family that sacrificing her needs makes her happy, she conditioned them to accept her “services” as a matter of fact. For years, she partook in these family dynamics without any reservations. But recently, she finds herself getting upset with her family members for the most trivial reasons. She told me they constantly “get on her nerves”. Many evening and weekends, once a bastion of family bliss, she is sulking, feeling disappointed and empty. She feels that nobody in her family respects her, that they do not care about her and that she is “merely a maid” in her own house. When I met with her husband, he was very aware of this situation. He had been telling her for quite some time to start taking care of herself. He tried to convince her that their children and him do not really need this selfless attention from her. Instead of appreciating his understanding, Marcia responds in angry outbursts and hurt feeling: She accuses him of being unappreciative of her efforts; she feels her family does not need her, and grows increasingly morose at feeling disposable and useless. She often feels angry with herself for being such a “patsy”.

In midlife, Marcia finds herself trapped in her own lie. We are not meant to be selfless: Quite the contrary, our first responsibility is to take care of ourselves. When you think about it, the opposite of selfless is not selfish; it is self-fulfilled. Those who make selflessness a central virtue in their lives are locked in a paradox: they ostensibly fulfill their needs by denying them to themselves. Noble as selflessness may seem, it carries with it a concealed need: the need to be recognized as a “martyr” by the beneficiaries. However, the mere requirement for recognition spoils the mantle of selflessness which creates a “Catch 22”. By presenting ourselves as giving and kind to the exclusion of our own needs, we trap ourselves into maintaining an impossible image. Over time, our need for recognition of our sacrifice by those around us exceeds the others’ ability to be grateful: They simply get used to our generosity! Fulfilling others’ needs at the exclusion of our own, while contending ourselves with this position is humanly impossible. Sooner or later we find ourselves bitter and angry and trapped.